Magic: The Gathering artist Liz Danforth joins Magic Untapped for a Q&A.

For more than 40 years, Liz Danforth has been a staple artist, writer, and scenario designer for a multitude of fantasy and sci-fi genre games and books. While she has done work for the Magic: the Gathering collectible card game, she has also gone into series ranging from Star Trek to Lord of the Rings to the Wasteland series.

Liz was kind enough to take some time out of her busy schedule to participate in a little Q&A about her her distinguished career, MTG artwork, and (of course) Art Nouveau.

Magic Untapped: What inspirations and influences in your life drove you to becoming a professional artist?

Liz Danforth: I came into this work from many different directions. My parents and older siblings did many and varied arts and crafts: drawing and painting, ceramics, lapidary work and small sculptures, mosaics, and fiber crafts of all kinds. I was able to experiment with all this and more, and encouraged to do so. I didn’t think I was especially good but of course they were all older and more experienced. By comparison to them, I had so much to learn! That served me well, making me try harder and explore everything.

What didn’t serve me as well was being told that I should develop “my own style” and not take art classes. Consequently, I am largely self-taught, but it meant that I had to kinda reinvent the wheel. Might I have been more accomplished, and sooner, had I been willing to pursue a formal art education? Instead, I was got an academic education -- a bachelors in Anthropology and (much later) a masters in library science.

That said, people liked my art enough to pay for it, starting in high school. I discovered hobby gaming in college, and people had me to drawing their role-playing characters. Soon after graduation, I was hired to work for Flying Buffalo Inc, the publisher of Tunnels & Trolls, the second-oldest fantasy role playing game. Rick Loomis of FBInc mentored me as the art director, and eventually had me running the entire publications department. He also allowed his people to work freelance for other companies, so I got to play with all manner of game settings, for many publishers. That earned me induction into the Academy of Gaming Arts and Design Hall of Fame in 1995. And eventually that creative freedom led to my work for some of the earliest decks of Magic.

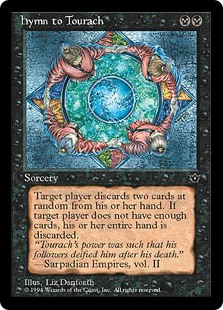

MU: You've done artwork for a number of notable Magic cards, including Glacial Chasm, Giant Badger (one of the game's first-ever promo cards), Merchant Scroll, and (probably most noteworthy) Hymn to Tourach. Specific to that last one, we've heard it was one of your most challenging. Could you tell us about it?

LD: I think this is a misconception, and I’m not sure where it comes from. All creative work is an exercise in iterative problem-solving, whether it’s a painting, a novel, a play, a poem, or composing a piece of music. Hymn was not so different in its challenges except insofar as every work is a different collection of problems to solve.

LD: I think this is a misconception, and I’m not sure where it comes from. All creative work is an exercise in iterative problem-solving, whether it’s a painting, a novel, a play, a poem, or composing a piece of music. Hymn was not so different in its challenges except insofar as every work is a different collection of problems to solve.

Perhaps this impression grew from one of the first problems I had to solve for Hymn, a story I’ve told before: what am I going to draw? My assignment came from Sandra Everingham, a last-minute request as we were tearing down our booths at the end of a GenCon or Origins. “Hey Liz, can you do another card for us?” … sure, what is it? … “Hymn to Tourach” … what’s that?... “oh, three or four wizards working together to cast a spell.” … okay, you got it.

On the plane ride home, I was trying to visualize how I could do that, and soon realized my quandary. If the wizards were in a circle facing each other, then no matter where I put the mental camera, I was looking at someone’s butt. I spun that visual around and around, until finally the “camera” swung up overhead. Looking straight down on the top of the spellcasters’ heads, I had my starting point.

When it came time to do the sketch, I had my then-boyfriend stand at the bottom of the stairs so I could grasp exactly how a person looked from that point of view. I had him turn 45º with his hands out like he was holding hands with someone, turn and turn again. Then I made him fatter, skinnier, and changed his hair so there were four mostly-different people as the summoners. His belted dressing gown became the red robes of the cultists.

MU: For Fifth Edition, you created new artwork for the reprints Fallen Empires' sac lands (Dwarven Ruins, Ebon Stronghold, Havenwood Battleground, Ruins of Trokair, and Svyelunite Temple). What is it like for an artist when they are asked to create new artwork for existing cards -- in this case, replacing the artwork that was created by Mark Poole for the cards' original printing?

LD: You’re making the incorrect assumption that I knew about the previous cards. I didn’t.

I played Magic, early on, because WotC gave us boxes of product in the early days instead of the Artist Proofs. I was enthralled by the other artists’ work but didn’t really twig to very many of their names. I am friends with Mark now, and respect him mightily, but that artwork of his didn’t hit my radar back then.

MU: How long do you typically spend on a piece?

LD: I’ll ask you a question in return: how long is a piece of string?

As I said above, every painting is a little different. Am I working on more than one assignment at a time? Is the deadline “Yesterday” or is it “Meh, before the end of the month would be nice”? How much is on my plate, so do I have to be superefficient or is this something I can give extra time to? Is a given painting giving me problems, or is it going oh so smoothly? Is the composition complex or simple? Am I doing something unusual for this piece, that might slow me down as I feel my way forward? Have I been sick? Do I have a new puppy in the house?

Any of these things could change the answer. I could give you a number but it would be as meaningless as “string is this long.” Some pieces go faster than others but, for me, a piece is done when it is done, and it takes the time it takes. I must be mindful not to invest too much more time than I am being paid for, of course. But my bottom line is “Am I proud of this?” before I let it go out the door.

MU: Have you ever tried a more "out of the box" approach to a card where you try a new perspective or style?

LD: You make it sound like that would be weird. I believe most artists experiment and stretch. There’s always more to explore, to learn. I must deliver what the art director has asked for, and what they expect of me, but I also get to make myself happy in the process.

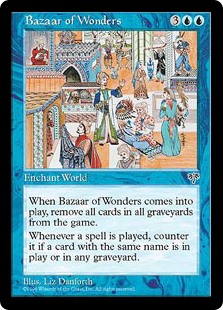

I did one excruciatingly detailed card art for Iron Crown’s Middle Earth card game, back in the day. I did it with hatchwork colored inks because I couldn’t paint the details of the Mines of Moria otherwise. Similarly, Magic’s Bazaar of Wonders is also inkwork to echo the look of Middle Eastern illuminated manuscripts.

I did one excruciatingly detailed card art for Iron Crown’s Middle Earth card game, back in the day. I did it with hatchwork colored inks because I couldn’t paint the details of the Mines of Moria otherwise. Similarly, Magic’s Bazaar of Wonders is also inkwork to echo the look of Middle Eastern illuminated manuscripts.

I’ve done card art that’s highly gestural and abstracted – not something “allowed” much nowadays. If I felt the card’s concept benefits from unusual treatment, then that’s what I do. Even something as “ordinary” as Hymn to Tourach has textures created with plastic wrap, with salt, and with a sponge instead of a brush.

Asking about a new perspective – well, as answered above, I had not done a top-down view until I did it for Hymn. I did it again for the [MicroProse] card Gem Bazaar and a high-angle view for the giant’s shadow looming over the hapless nerk in Shrink. And Bazaar of Wonders was different because the setting itself called for something different. I try to be adaptable and flexible. Isn’t that implicit in working creatively in the first place?

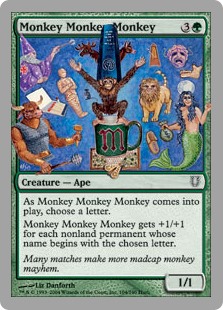

MU: In 2004's Unhinged, you created some rather fun artwork for a pair of cards: Monkey Monkey Monkey and Symbol Status. What was the experience like creating card art for an Un-set as opposed to a traditional Magic set?

LD: Honestly, I didn’t really grok how different the card set was intended to be. I was told not to take it “as seriously” but really, I treated it much the same as any other assignment.

LD: Honestly, I didn’t really grok how different the card set was intended to be. I was told not to take it “as seriously” but really, I treated it much the same as any other assignment.

MU: Do you have a favorite art medium? If so, does it make fantasy artwork harder or easier to create?

LD: Let’s start with paintings. My preference for acrylics grew from the need to finish a piece, then pop it into a FedEx envelope to mail it out an hour later! Now we have easy access to scans. Back then, I had to mail the original, or get an oversized photo-quality transparency with color bar shot at a big print and reproduction shop. That was time consuming as well as costly.

I still do a lot of black and white ink illustration, and (in some circles) that is still what I am best known for. I like the pure composition and linework of inks, controlling contrast, light and shadow. Hue and chroma, color temperatures are more complex. Thus, painting is more challenging, with many more creative problems to be solved in every piece.

I’m glad I get to do both. Both are rewarding in different ways, although color paintings get all the respect from the general public. Inkwork, not so much, which is a bit of a shame.

I occasionally do oils, and I play with watercolors, gouache, and various 3D media like ceramics and mosaics. I call myself “a maker” because “artist” doesn’t really cover all the bases. I relish creating something that didn’t exist when I woke up that morning. That includes fiction and game design work for tabletop and some computer games (writing, not art), and professional editing as well.

MU: What kinds of things are more tricky for you to create (landscapes, people creatures, etc.)?

LD: In my experience, artists seem to gravitate either toward organic forms, or are at their best with mechanical or architectural forms. I am an organic forms artist. The strictures of proper perspective for mechanical forms just gives me fits. I have learned to do it, kinda, but it’s always a struggle.

Give me an imaginary fantasy monster, and I can make it believable in any contorted posture. I can usually envision how to pose humanoids, even foreshortened or expressing extreme gestures. The faces of a withered, centuries-old vampire or a dewy-eyed fae come as easily as breathing. Forests and marsh have personalities and sense of place. A tumble of rock has emotional implications.

Palaces and spaceships, cathedrals and cars and cyberpunk industrial wastelands? Hard for me. Swords and armor are fine, but battlemechs? Not so much.

The organic, curvilinear aesthetic of Art Nouveau (also called Jugenstil, Modernismo, or Liberty Style depending on the region of the world) informs a lot of my work, even when does not precisely fit the assignment. You can see hints of it in the organics of Svyelunite Temple, or the natural forms of Ebon Stronghold.

MU: Do you have any future projects you are excited about?

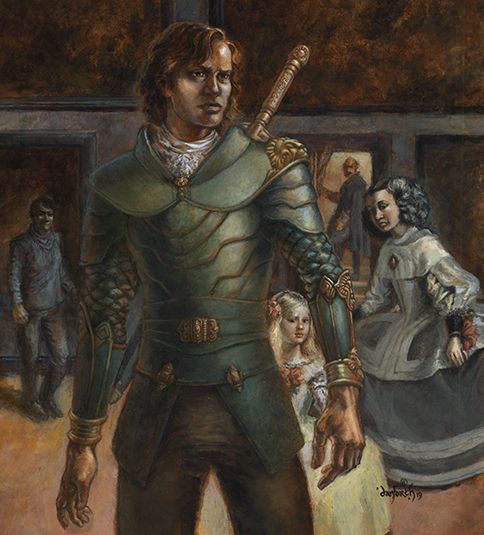

LD: I am jazzed up about Grindgear’s upcoming card game Sorcery: Contested Lands. The art director sought out many of Magic’s early artists, and asked us to do new paintings. After all, we are decades more practiced and experienced now. He specifically wanted traditional brush-and-paint art, not digital works.

I [don't] disparage all digital art; some is glorious. I use Photoshop among my many tools, at times. But the learning curve for pure digital work has been more than I can shoehorn into my schedule. And frankly, I think the new paintings for Sorcery are among the very best works I have ever done. I’ve been able to take my time on every piece, and I’ve been asked to do things (like landscapes) not typically within my wheelhouse. It has been exciting using photo references I’ve taken from trips made (pre-pandemic) to attend Magic tournaments in Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and elsewhere. Some pieces have been profoundly inspired by museum visits to the Prado in Madrid, or the Uffizi in Florence.

I’ve done half a dozen paintings for this project, and wish I’d had time for more.

Nothing will completely replace Magic, nor would I want that. But I believe this project will enthrall players as completely as Magic did when it first came out. I am proud to be a small part of this game, and I hope it thrives so I can do many more paintings for years to come.

That said: I would be remiss not to mention my on-going work for Flying Buffalo’s Tunnels & Trolls projects. Flying Buffalo has been bought by a new corporation, Webbed Sphere, after FBInc’s Rick Loomis passed away not too long ago. I also do art for Steve Jackson Games [The] Fantasy Trip, where people remember my earliest artwork with bell bottoms on the adventurers. (I didn’t draw feet very well back then. The pants hid the problem! I draw feet just fine now.)

I encourage your readers to look at my Patreon page, which is where I am most active. About a third of my posts are open for everyone to read, not just supporters, so you can get a taste of what I have to offer. I tell stories, talk about works in progress, and sometimes share digital or physical artworks as occasion warrants. Patreon enables me to do work I could not take the time for otherwise. And I am inspired to try harder and experiment to earn the trust my supporters express by funding me there. We have a lovely, lively Discord community, and weekly live meetups as well.

My official website is woefully out of date although I am working on updating it. I occasionally tweet from @LizDanforth but almost never go to Facebook any more. (Messages there will probably get lost in the ether.) I am always as close as an email (

Thank you to Liz for participating in this interview.